Chasing a bullet

For as long as I can remember I've always been fascinated by everything to do with space. Recently, I tore through Mike Massimino's book Spaceman and now am reading The Interstellar Age, which is about NASA's Voyager 1 & 2 missions. My daughter delights in watching Commander Chris Hadfield's videos from the International Space Station so much that we've seen every one many many times, and I've watched both series of Cosmos multiple times. Since I am a certified Space Geek, it's only natural that I try to combine that with my passion for photography.

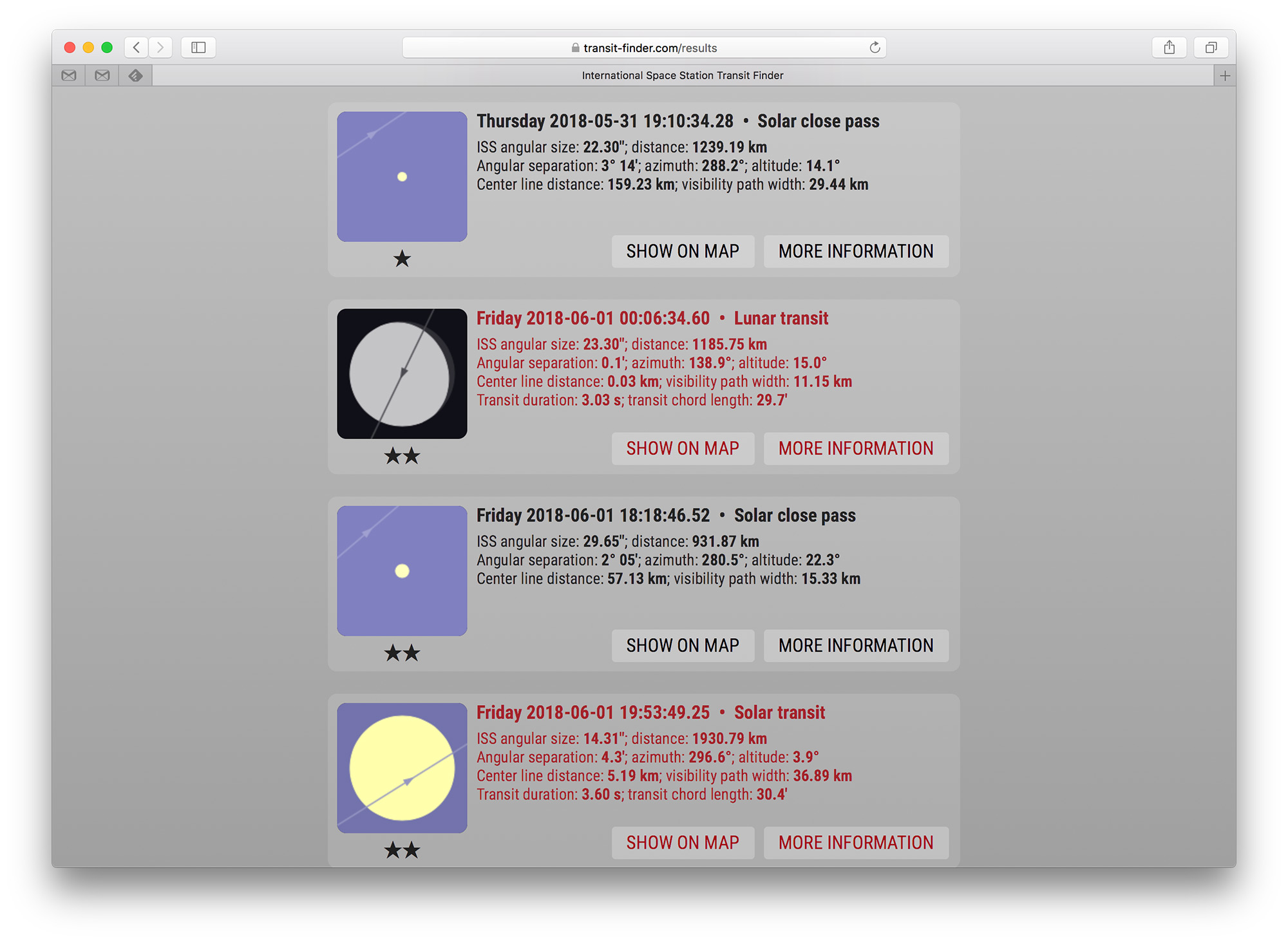

One of the coolest photos I have ever seen is of the Space Shuttle docking with International Space Station while in transit past the sun, but I always wondered how on earth did they do that? Could I do that? The station itself is orbiting the earth 250 miles up moving at 17,500mph, which makes photographing it like chasing a bullet. The first hurdle was to find a tool to tell me where and when it would be. After some searching I stumbled across Transit Finder which when given lat/long and date range would tell me exactly where and when I needed to be down to the millisecond.

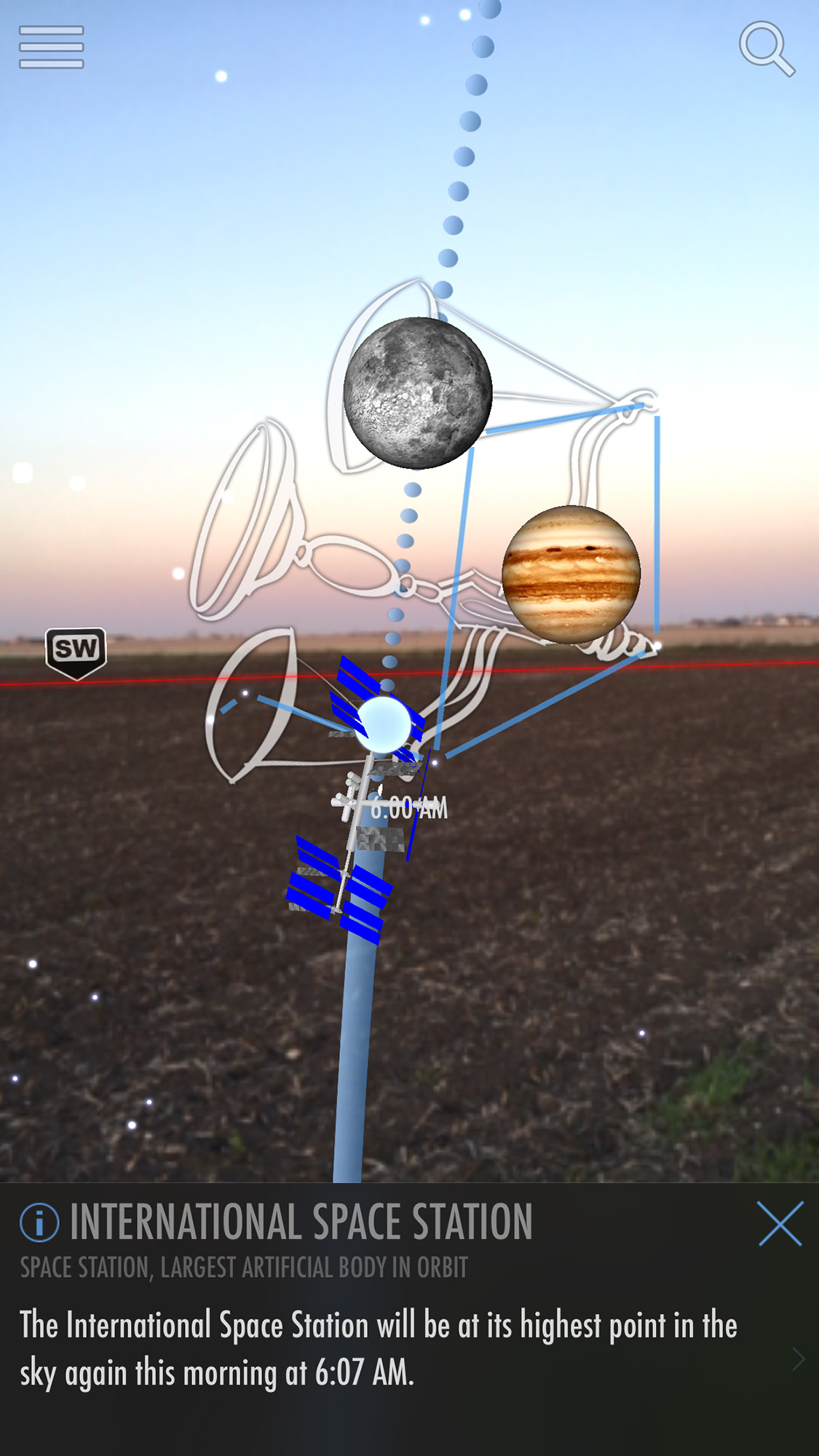

Not surprisingly, options are limited if you don't want to travel a few hours to make an attempt. I checked the site weekly for at least a year, but most opportunities slipped by due to scheduling conflicts or just poor weather. I finally made my first attempt a month ago on May 1st at sunrise. I rolled out of bed at 4:30 and drove 45 minutes south to see if I could capture the ISS just before moonset set. To track the path of the ISS I used an iPhone app called SkyView Lite, and everything looked perfect. I was ready.

I checked my phone a few more times, and when I got about two minutes out I just sat there, staring through the camera's eye piece watching as hard as I could. Waiting. Waiting. Waiting. Nothing. Checked the app again and the ISS had blown right past - I had no idea if it was close, I never even spotted it. I was disappointed, but determined to figure out what happened. When I got home I realized that at the time the ISS was illuminated and would have appeared as a white spot reflecting sunlight, while I was looking for the distinct black silhouette. Okay, rookie mistake. I made a note and went back to checking Transit Finder every few days.

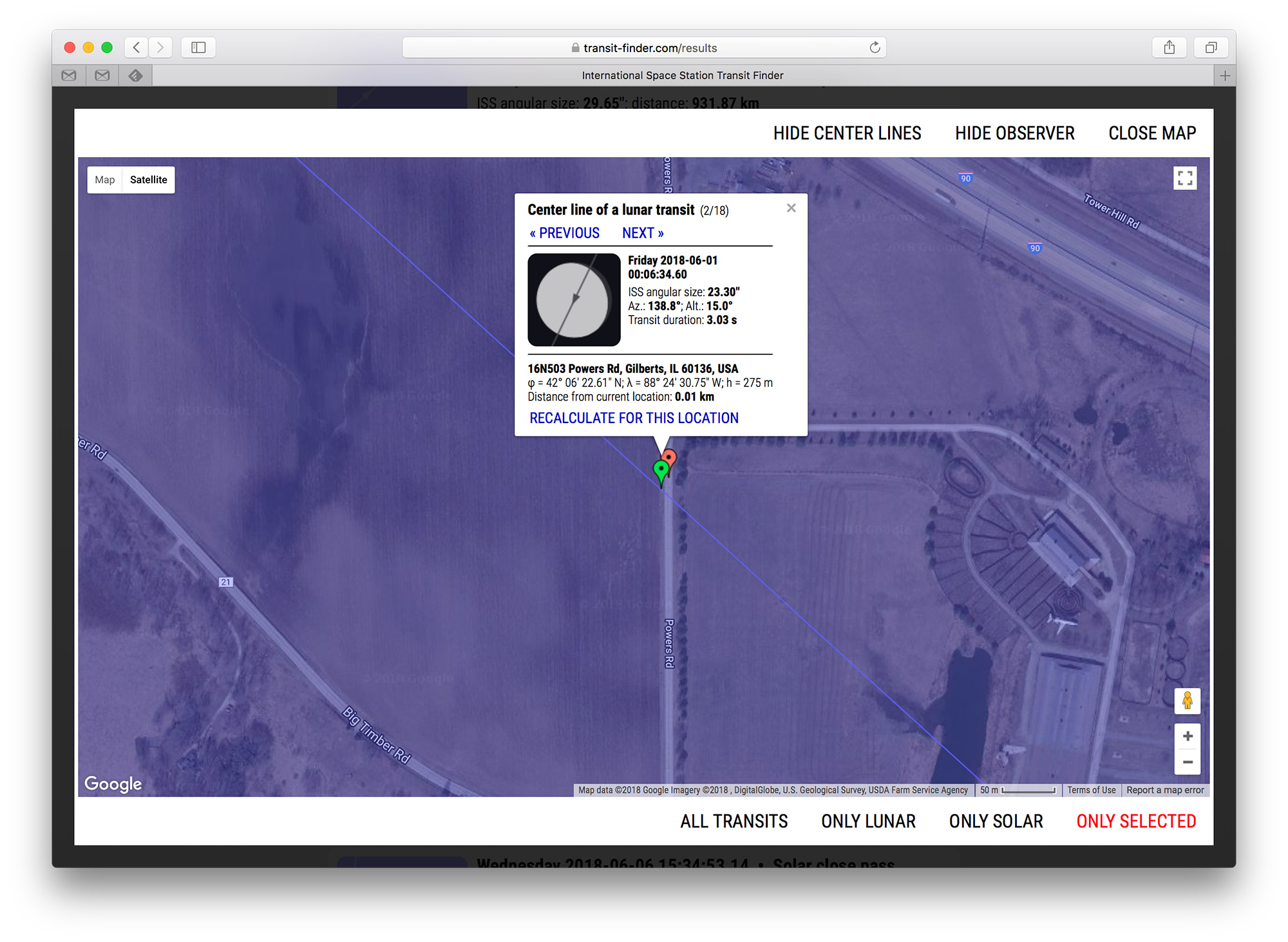

Finally two weeks ago I saw a favorable opportunity where I could get to the center line only having to travel about 25 minutes from home, and 12:06pm was reasonable. I plotted out three backup sites just incase of unforeseen impediments. The spot I chose was a back road off the beaten path where I could setup and hopefully not be bothered. I had the time, I had the place, now the only x-factor was the weather.

That night I packed up my gear and despite some intermittent clouds, headed out. I found the location easily enough thanks to scouring Google Maps a few times a day during the past week. Checking SkyView Lite I was a bit confused - the ISS was tracking to rise in the West just a few minutes before it was due to cross the Moon in the South East. I still setup my gear but kept an eye on the station wondering if the app was wrong. I knew it travelled fast but didn't realize it would shoot horizon to horizon in a matter of minutes. By the time I got the telescope setup and tracking the Moon I checked SkyView again and saw the ISS was already directly at the zenith and headed to intersect the Moon at an alarming pace.

Just like my first attempt I had my eye glued to the eyepiece for a few minutes, concentrating on where the station should begin it's transit. I glanced up once or twice to see if I could catch it with my naked eye, but no luck. Finally I spotted it coming out from between the Sea of Serenity and the Sea of Tranquility, and mashed the remote cable release. I successfully got nine frames of the ISS transiting the Moon.

I checked the image previews as fast as I coulld and let out a yell. I had gotten it! It's angular size was 27.46" so it was much smaller than ideal, but you could still see the distinct shape cutting across the lunar surface. After importing the images and doing some minor tweaks, I stacked them in Photoshop and set the blending mode to stack each frame together, creating the final composite.

Looking at other opportunities in Transit Finder I realize that the stations angular size can vary from the low 20s all the way into the 60s, meaning it would appear two to three times bigger in ideal conditions. I'm going to keep trying for some better results and will probably try a solar transit at some point. Anyway, as Neil deGrasse Tyson always says, keep looking up!